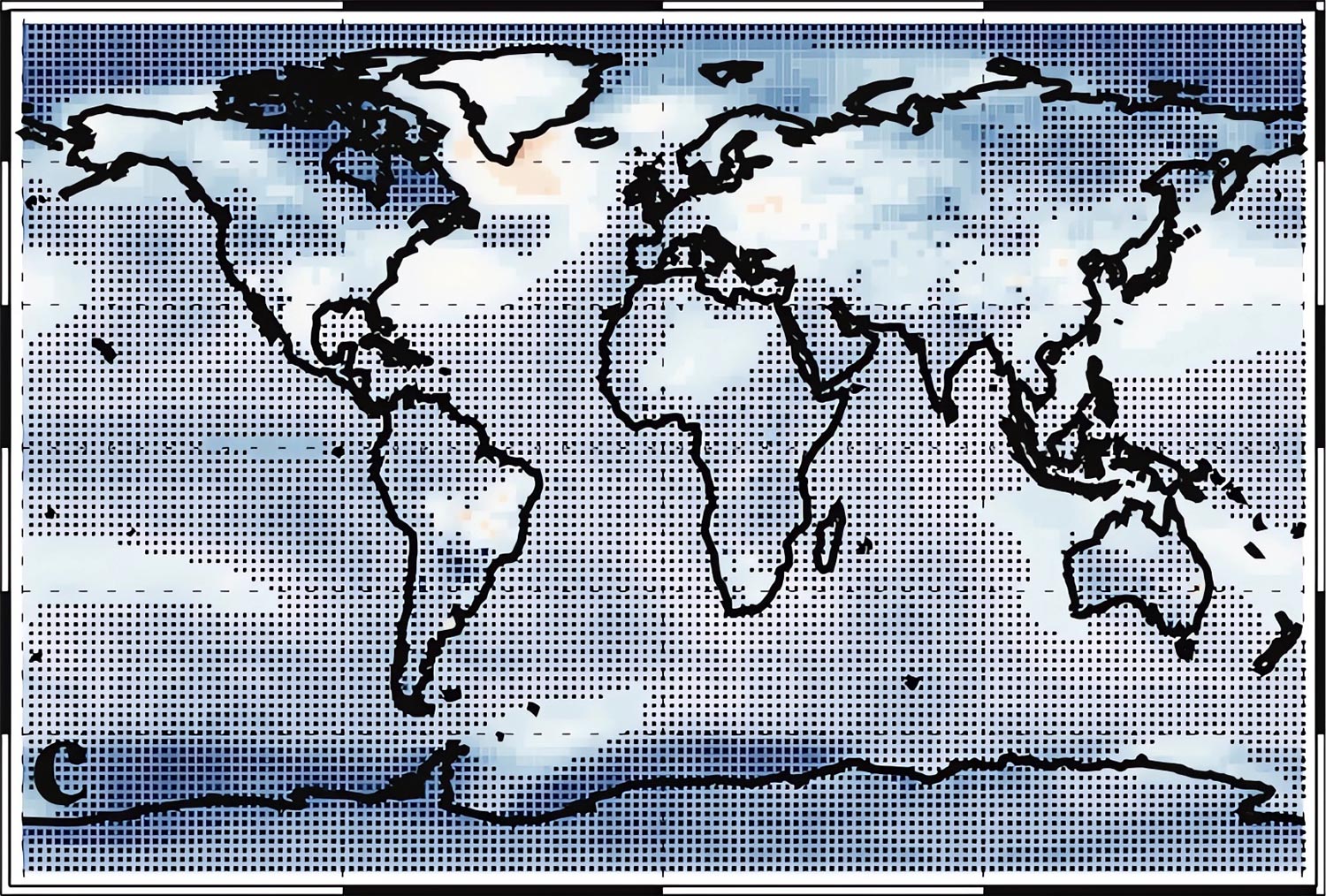

Średnia reakcja temperatury powietrza przy powierzchni na metan, zanika tylko do efektów krótkofalowych. Źródło: Robert Allen/UCR

Silny wpływ gazów cieplarnianych: nieco mniejszy niż wcześniej sądzono.

Naukowcy z UC Riverside odkryli, że metan nie tylko zatrzymuje ciepło w atmosferze, ale także tworzy zimne chmury, które kompensują 30% ciepła. Absorpcja energii krótkofalowej przez metan odwracalnie powoduje efekt chłodzenia i zmniejsza wzrost opadów o 60%. Wynik ten podkreśla potrzebę uwzględnienia wszystkich znanych skutków gazów cieplarnianych w modelach klimatycznych.

Większość modeli klimatycznych nie uwzględnia nowego odkrycia Uniwersytetu Kalifornijskiego w Riverside: metan zatrzymuje dużo ciepła w ziemskiej atmosferze, ale tworzy również zimne chmury, które kompensują 30% ciepła.

Gazy cieplarniane, takie jak metan, tworzą rodzaj koca w atmosferze, zatrzymując ciepło z powierzchni Ziemi, zwane energią długofalową, i zapobiegając jego emisji w kosmos. To sprawia, że planeta jest gorętsza.

„Koc nie generuje ciepła, chyba że jest elektryczny. Czujesz ciepło, ponieważ koc blokuje zdolność twojego ciała do wysyłania ciepła do powietrza. To ta sama koncepcja” – wyjaśnił Robert Allen, adiunkt nauk o Ziemi na UCSD.

Okazuje się, że oprócz pochłaniania energii długofalowej metan pochłania również energię słoneczną, zwaną energią krótkofalową. „To powinno ogrzać planetę” – powiedział Allen, który kierował projektem badawczym. „Jednak w przeciwieństwie do tego, czego oczekiwano, pochłanianie fal krótkich sprzyja zmianom w chmurach, które mają lekki efekt chłodzenia”.

Średnia reakcja temperatury powietrza przy powierzchni na metan, czynnik rozkładający na (a) efekty długofalowe i krótkofalowe; b) tylko efekty długofalowe; oraz (c) tylko efekty krótkofalowe. Źródło: Robert Allen/UCR

Efekt ten jest szczegółowo opisany w czasopiśmie NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Methane changes this equation. By holding on to energy from the sun, methane is introducing heat the atmosphere no longer needs to get from precipitation.

Additionally, methane shortwave absorption decreases the amount of solar radiation reaching Earth’s surface. This in turn reduces the amount of water that evaporates. Generally, precipitation and evaporation are equal, so a decrease in evaporation leads to a decrease in precipitation.

“This has implications for understanding in more detail how methane and perhaps other greenhouses gases can impact the climate system,” Allen said. “Shortwave absorption softens the overall warming and rain-increasing effects but does not eradicate them at all.”

The research team discovered these findings by creating detailed computer models simulating both longwave and shortwave methane effects. Going forward, they would like to conduct additional experiments to learn how different concentrations of methane would impact the climate.

Scientific interest in methane has increased in recent years as levels of emissions have increased. Much comes from industrial sources, as well as from agricultural activities and landfill. Methane emissions are also likely to increase as frozen ground underlying the Arctic begins to thaw.

“It’s become a major concern,” said Xueying Zhao, UCR Earth and planetary sciences Ph.D. student and study co-author. “We need to better understand the effects all this methane will bring us by incorporating all known effects into our climate models.”

Kramer echoes the need for further study. “We’re good at measuring the concentration of greenhouse gases like methane in the atmosphere. Now the goal is to say with as much confidence as possible what those numbers mean to us. Work like this gets us toward that goal,” he said.

Reference: “Surface warming and wetting due to methane’s long-wave radiative effects muted by short-wave absorption” by Robert J. Allen, Xueying Zhao, Cynthia A. Randles, Ryan J. Kramer, Bjørn H. Samset and Christopher J. Smith, 16 March 2023, Nature Geoscience.

DOI: 10.1038/s41561-023-01144-z

„Odkrywca. Nieprzepraszający przedsiębiorca. Fanatyk alkoholu. Certyfikowany pisarz. Wannabe tv ewangelista. Fanatyk Twittera. Student. Badacz sieci. Miłośnik podróży.”